Could China Have a Reserves Crisis?

17th February 2016

Could China Have a Reserves Crisis?

Last summer, U.S. lawmakers were condemning China for pushing down its currency, arguing that it was still “terribly undervalued.” But those days may be long gone. Chinese and foreigners alike have been stampeding out of RMB, leaving the Chinese central bank struggling to keep its value up and prevent a rout.

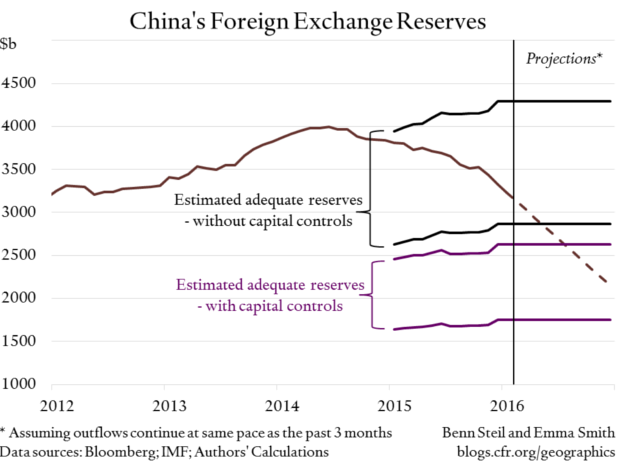

The People’s Bank of China has been selling off foreign currency reserves at a prodigious rate to keep the RMB stable. At $3.2 trillion, China’s reserves still seem enormous. But they are down $760 billion from their 2014 peak, and $300 billion in just the past three months. As shown in the figure above, at the current pace of decline China’s reserves will, according to the IMF’s framework for reserve adequacy, actually fall to a dangerously low level in the spring. This means that China would be at risk of a balance-of-payments crisis, unable to pay for essential imports or service its dollar debt payments.

China has for years been pursuing what has been called the “Impossible Trinity”: controlling interest and exchange rates while leaving the capital account significantly open. Chinese residents are permitted to send up to $50,000 overseas annually – this is enough to allow trillions in outflows. So what can China do to staunch the rapid decline in reserves?

It could impose tighter capital controls, as Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda controversially urged it to do. As shown in the figure, this would allow China to operate safely with fewer reserves. But it would also put a halt to China’s plans to transform the RMB into a major reserve currency.

China could also raise interest rates, which might encourage capital inflows and discourage outflows, but this would hurt growth in an already sinking economy.

Finally, China could let the exchange rate fall significantly, but this would increase the debt burden on Chinese companies. Outstanding dollar credit to Chinese non-financial companies is estimated to be around $1 trillion. Too great a fall in the RMB, coupled with slowing economic growth, could precipitate a corporate solvency crisis.

That China has no good options, and only a choice among painful ones, reflects the underlying structural problem in the Chinese economy – one that will take many years to fix. The economy was tooled to support what have been shown to be grossly overoptimistic expectations of foreign demand for Chinese exports. Retooling the economy to encourage domestic demand will require time and a willingness on the part of the Chinese government to allow businesses to die so that more promising ones may live.

It also shows that American charges that China’s currency was massively undervalued were based on the flawed assumption that capital would want, indefinitely, only to get into China and not out. It’s a sure bet no one in Congress will be calling for China to float its currency again anytime soon.

This article is reproducd with kind permission of the authors and the Council on Foreign Relations. The original article can be found here.

See also How the Yuan Crisis Could Forge a New Currency Order

by the Peterson Institute for International Economics